How Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) can be used in sport

Nov 07, 2024By Peter Sweeney

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to briefly describe how the science of applied behaviour analysis (ABA) can support individuals and teams in the world of sport. Understanding the basic principles and science of ABA can empower athletes and coaches to gain a greater understanding of their own behaviour in an attempt to improve on those behaviours. Professionals with a background in ABA can support and complement other professionals such as sports scientists, sports psychologists, performance analysts, nutritionists, coaches, managers etc. Concepts, principles and procedures derived from ABA can enhance athlete performance as well as performance of coaching staff and the overall team.

Areas that are frequently focused on include teaching new skills, improving performance, teaching coaching techniques, promoting adherence to team goals, decreasing errors and decreasing negative and/or unwanted behaviours. This paper will give a brief insight into the history of ABA. It will discuss procedures of ABA that support the development of new behaviours as well as procedures that can support a decrease in unwanted behaviours. While discussing the science I will try to give examples of how ABA can be applied in the world of sport. The following sections are included in this paper:

- Brief history of ABA

- Seven dimensions of ABA

- Behaviour

- Behaviour in Sport

- The four stages of ABA intervention in sport

- Basic principles of ABA

- Procedures to support behaviour change in sport

- Generalisation and social validity in ABA

Brief history of ABA

| ABA is a natural science that aims to enable individuals to develop skills that will improve their overall quality of life (Keenan et al., 2015). |

Behaviour analysis is the study of behaviour and the variables that influence behaviour. Behaviour analysts work in both experimental and applied fields, sometimes studying behaviour principles in the abstract, or applying the principles of behaviour analysis in an attempt to solve specific behaviour difficulties (Grant and Evans, 1994). Behaviour analysis is a unique profession as practitioners can be employed to support individuals in a wide variety of occupations, such as in sport, business, education, treatment of substance abuse, and is probably best known for its effectiveness in supporting individuals with autism spectrum disorder, learning difficulties and other disabilities.

ABA is the applied branch of behaviour analysis which can be traced back to the year 1959. There have been countless publications of peer reviewed research outlining its effectiveness (Kerr et al., 2000). ABA is a natural science that aims to enable individuals to develop skills that will improve their overall quality of life (Keenan et al., 2015). Behaviour analytic approaches and procedures are illustrated by an emphasis on doing rather than knowing (Fisher et al., 2011). ABA delivers a systematic method to planning, executing, and evaluating instructions based on tested principles that describe relationships between stimuli in the environment (e.g., coach shouting at a team member on the field) and changes in behaviour as a result of the environmental stimuli (e.g., athlete’s response) (Baer et al., 1968).

Individualisation (meeting the needs of the individual), empiricism (objective observation), replicable instructional practises, and a dynamic discipline grounded in constant experimentation are features from ABA that effectively support individuals (Dunlap et al., 2001). Analysing and adapting contingencies according to each learner’s performance on the task are also key features of ABA (Vargas, 2013). Instructional design, high rates of responses from participants, continuous feedback, and constant decision-making built on participant performance are procedures that generate excellent outcomes for individuals and are based on ABA procedures (Twyman and Heward, 2016).

Seven dimensions of ABA

The seven dimensions of ABA that ensure effective procedures are produced include applied, behavioural, analytic, technological, conceptually systematic, effective, and generalisable (Baer et al., 1968). These dimensions have allowed assessment and intervention strategies to be developed and successfully implemented in many settings such as in clinical, sports, education and business settings (Roane et al., 2015). The following is an overview of the seven dimensions of ABA:

- Applied: investigates socially significant (important) behaviours to the individual.

- Behavioural: actual objective, observable and measurable behaviour in need of improvement.

- Analytic: intervention decisions are data driven. If data shows that an intervention is not producing change in the desired behaviour, then a change is warranted. It demonstrates experimental control over the occurrence and non-occurrence of the behaviour and demonstrates a functional relation (i.e., behaviour changes because of the intervention implemented and nothing else).

- Technological: effectively described intervention procedures enhances effective replication by others.

- Conceptually systematic: interventions are derived from the basic principles of behaviour.

- Effective: behaviour changes sufficiently to produce practical results for the individual.

- Generality: produces behaviour changes that last over time, appear in other environments and/or spread to other behaviours.

Behaviour

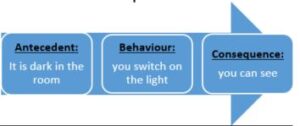

Behaviour is the activity of living organisms. It is the “portion of an organism’s interaction with its environment that involves movement of some part of the organism” (Johnston and Pennypacker, 1993, p.31). The environment (physical setting) influences behaviour by stimulus change. Stimulus is an energy change that affects an organism through its receptor cells. As behaviour is individualised, the experimental strategy of behaviour analysis features single-case (individual) methods of analysis. Respondent behaviour acts as a reflex that cannot be controlled. For example, when feeling hot, the body will sweat. Operant behaviour operates on the environment and is controlled by its immediate effects. It is selected, shaped, and maintained by the consequences that have followed it in the past. For example, when you are cold, you put on a jumper which results in you feeling warm. This consequence impacts the future frequency of this behaviour occurring again (e.g., next time you are cold, you put on a jumper). The three-term contingency (antecedent, behaviour, consequence) is regarded in behaviour analysis as the basic unit of behaviour and is how we can analyse future effects on behaviour (Cooper et al., 2020).

| Consequence:

Events or interactions which happen immediately after the behaviour |

| Behaviour:

Behaviour or sequence which has occurred |

| Antecedent:

Events or interactions that happen immediately before the behaviour occurs |

- Antecedent: a stimulus or event in a person’s environment that occurs immediately before a specific behaviour.

- Behaviour: the actions or reactions of a person in response to an external or internal stimuli.

- Consequence: a stimulus or event that immediately follows behaviour. Consequences impact the future likelihood of behaviour. Some consequences increase the likelihood that the individual will engage in the behaviour again in the future (reinforcement) while some consequences decrease the likelihood that the individual will engage in the behaviour again in the future (punishment).

For example:

| Therefore, the future frequency of switching on a light when it is dark will increase.

|

| Therefore, the future frequency of answering your phone while driving will decrease.

|

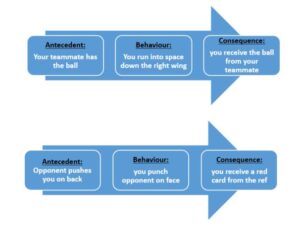

Three-term contingency example in sport:

| Therefore, the future frequency of running into space down the right-wing will increase.

|

| Therefore, the future frequency of punching an opponent on face after getting pushed will decrease.

|

Behaviour in sport

| ABA is a scientific, individualised, person-centred, data driven science that can support management teams to improve individual and team performance |

As mentioned previously, behaviour is the activity of any living organism. It is everything we do e.g., walking, shouting, lifting a pen, scratching hand etc. In terms of sport (GAA), examples of behaviour can include soloing, running, tackling etc. ABA is an individualised, person-centred approach that can be utilised in underage settings to support individuals to master skills such as the kick pass, hand pass, solo etc. At adult grade it can support the individual athlete to improve their behaviour on the pitch (e.g., positioning, turnovers, distance covered etc) and off the pitch (behaviour towards nutrition, strength and conditioning, recovery etc.). ABA can support coaches and management in assisting game plans and maximising the opportunity for successful implementation of procedures and strategies through the science of ABA. Working alongside other professionals such as performance analysts, statisticians, strength and conditioning coaches and management teams, ABA professionals can attempt to understand individual behaviour to aid them in meeting individual and team goals.

The four stages of ABA intervention in sport

| · Direct & Indirect assessment

· Observations · Collecting baseline data |

| · Monitor & evaluate program

· Make adjustments if required |

| · Selecting an appropriate based intervention

· Plan around available resources |

| · Work together with management team and player to implement program/intervention

· Observations · Continue to collect data |

The four stages involved in an ABA intervention include assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation. Direct (tests and direct observations) and indirect (interviews, checklists, rating scales) methods of assessment are used to identify, define and determine the function of target behaviours which are then measured. Measuring observable behaviour before, during and after intervention is imperative to evaluate intervention effectiveness and guide decisions around continuing, modifying or terminating the intervention. Collecting data to form a baseline informs the professional’s decision-making process while selecting an appropriate intervention. ABA therapists then implement the intervention which they monitor over time by evaluating the progress and making adjustments where and when required.

Basic Principles of ABA

- Reinforcement

Reinforcement is a basic principle of behaviour where a response/behaviour is followed immediately by a stimulus change that result in similar responses/behaviour increasing in the future. For behaviours we want to increase, it is extremely important that reinforcement follows immediately after the behaviour occurs (i.e., immediately after the behaviour occurs in training or games and not post training/games or team meetings).

- Positive reinforcement occurs when a response/behaviour is followed immediately by the presentation of a stimulus, and this results in more frequent similar responses/behaviour in the future.

- For example, a forward player runs to defence and completes a turnover. The presentation of the manager praising the forward player (positive reinforcer) means that it is likely that the behaviour of running back to help the defence will increase in the future.

- Negative reinforcement occurs when the removal of a stimulus leads to an increase in the future occurrence of a response/behaviour.

- For example, the coach shouts instructions at a player to run, player runs which results in the stimulus of the coach shouting instructions being removed. Therefore, when the coach shouts instructions in the future, it is likely that the behaviour of running will increase.

- Punishment

Punishment is a basic principle of behaviour where a response/behaviour is followed immediately by a stimulus change that result in similar responses/behaviour decreasing in the future. Effectively implementing positive punishment procedures can decrease inappropriate behaviour and increase responsiveness to reinforcement. However, several disadvantages can occur, such as other individuals engaging in modelling punishment procedures. For example, by provoking withdrawal in others, suppressing responses, promoting aggression and diminishing self-esteem. Moreover, punishment is often overused or incorrectly implemented. It is crucial to note that ABA professionals adhere to a strict ethical code that ensures reinforcement strategies are always used prior to any punishment procedure. If punishment is required, reinforcement must be used simultaneously.

- Positive punishment occurs when a response/behaviour is followed immediately by the presentation of a stimulus, and this results in the likelihood of a behaviour occurring again in the future decreasing.

- For example, a player kicks wide from outside the scoring zone, and coach shouts at the player. Therefore, in the future kicking from outside the scoring zone will decrease to avoid the coach shouting.

- Negative punishment occurs when removing a stimulus decreases the likelihood of the behaviour occurring again in the future.

- For example, the player kicks wide again from outside the scoring zone, the coach removes the player from the pitch, and in the future kicking wide from outside the scoring zone decreases. Therefore, in the future kicking a wide will decrease to avoid being removed from the pitch.

- Extinction

Extinction is a basic principle of behaviour where reinforcement of a previously reinforced behaviour is discontinued. The primary effect is a decrease in the frequency of the behaviour until it reaches a pre-reinforced level or ceases to occur completely. Extinction can be seen in everyday life.

- For example, you keep pushing the on button on your television but the television does not come on (reinforcer withdrawn), therefore you stop pushing the on button on your tv remote.

- Another example is you post daily on Facebook; you like to see the number of likes and comments you get on your posts. Overtime, people stop liking and commenting on your posts (reinforcer withdrawn). Eventually, you give up posting on social media as you no longer get any reactions.

As an example, in sport, let’s say a young kid is frequently being substituted during matches. We conduct an ABC analysis to assess why this behaviour is occurring:

- Antecedent: player receives the ball

- Behaviour: player kicks his/her fifth wide of the match from outside the scoring zone

- Consequence: player is removed from the pitch

We notice the behaviour of the young kid kicking five wides from outside the scoring zone is frequently occurring during each match. Therefore, kicking five wides is being maintained by negative reinforcement (removal from the pitch), when the coach may have believed removal from the pitch to be punishing. As the behaviour is occurring more regularly, being removed from the pitch is in fact, reinforcing this behaviour. If we were going to place this behaviour on extinction, we would withdraw the reinforcer completely. That is, when the player kicks five wides, we do not remove him/her from the pitch. Eventually, kicking five wides will decrease completely because the player is no longer getting the outcome they desire.

Procedures to support behaviour change in sport

A behaviour change procedure is a research-based, technological, consistent method for changing behaviour that has been derived from one or more basic principles of behaviour. Behaviour change procedures enable professionals to support individuals to:

- Develop new behaviours

- Decrease unwanted behaviours

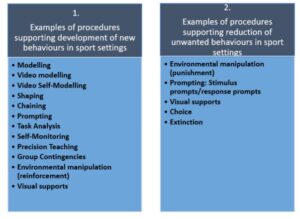

- Examples of behaviour change procedures that can support individuals to develop new behaviour in sport settings include:

Modelling: learners acquire new skills by imitating demonstration of the skills. The model demonstrates the exact behaviour the learner is expected to perform. The target behaviour is occasioned by another person’s model of the behaviour. The target behaviour is modelled closely in time and the model is the primary controlling variable for the imitative behaviour. An imitative behaviour is a behaviour emitted following an antecedent event (i.e., the model). E.g., coach modelling the skill of the hand pass.

Video modelling: the individual views a video of a model performing the target behaviour and then imitates the behaviour e.g., using technology to showcase a model performing how to complete a tackle.

Video self-modelling: the individual views a video of him/her successfully performing the target behaviour and then imitates his/her own model e.g., coach records the player performing the skill and then evaluates the recording to improve performance.

Shaping: involves the differential reinforcement of successive approximations to the target behaviour e.g., when teaching a child how to pass a ball to his teammates, you provide reinforcement for the behaviour of touching the ball with the foot, then for touching the ball with the foot and kicking and then touching the ball with the foot and kicking to a team mate. Reinforcement is provided for each successive approximation of the terminal target behaviour (passing the ball to a team mate).

Chaining: a method for linking specific sequences of responses to form new performances e.g., the sequence of a hand passing training drill: start at cone, jog to next cone and receive the ball from teammate, jog to next cone and handpass to another teammate.

Prompting: can be used to increase the probability that the desired response occurs:

Stimulus prompts (A prompt that makes the stimulus more obvious):

- Movement cues (e.g., pointing, touching, looking)

- Positional prompts (e.g., moving target stimulus)

- Gestural prompts (e.g., using a gesture to prompt the action or target stimulus)

- Intrinsic prompts (e.g., colour, size, shape)

Response prompts: (A prompt that acts on the response of the learner):

- Verbal instruction (can also be pictures, written words, or signs)

- Modelling (e.g., coach, peer or self-modelling)

- Physical guidance (e.g., partial physical, full physical)

- Time delay (e.g., waiting before presenting prompt)

Task Analysis: the process of breaking a complex skill into smaller more achievable teaching units e.g., the skill of the kick pass is broken down into smaller teaching units (i.e., head down, eyes on ball etc). Visuals of each step can support the process.

Self-monitoring: a procedure where the individual observes his/her own behaviour and records the occurrence or non-occurrence of a target behaviour e.g., via video analysis, stats etc.

Precision teaching: an instructional approach that involves increasing fluency of a target skill.

- Pinpointing the skills to be learned

- Measuring the initial frequency at which the individual can perform those skills

- Setting a goal for improvement

- Using direct, daily measurement to monitor progress made under instruction

- Charting the results

- Evaluating the program and making adjustments if required

Group contingency: a contingency in which reinforcement for all individuals in a group is dependent on the behaviour of:

- An individual within the group

- A select group of individuals within the larger group

- Each individual of the group meeting a performance criterion

Visual supports: a visual tool presented to support the individual. They can be used to prompt or prime a desired response. This can include, but is not limited to pictures, written words, transitional cues, schedules, gestures and choice boards. For example, the calendar in your phone is a visual support, and wearing a wrist support with a motivational quote is also a visual support.

(Cooper et al., 2020)

- Examples of behaviour change procedures that can aid a decrease in unwanted behaviours in sport settings include:

There are many procedures available to aid decreasing or eliminating unwanted behaviours. Some undesired side effects can occur from interventions based on punishment or extinction procedures (see punishment section). Additionally, implementing extinction and punishment procedures as primary methods of intervention for reducing unwanted behaviour does not teach the individual adaptive positive behaviour. Therefore, it is crucial to replace unwanted behaviours with appropriate replacement behaviours while teaching skills when attempting to decrease unwanted behaviours. For example, if a manager wants to decrease kick passes going astray during games, it is important that he/she trains the players to improve kick passing or replace kick passes with hand passes.

Antecedent interventions in the form of environmental manipulation alters the environment in specific ways to improve the behaviour. (Note that some behaviour change procedures can be utilised to decrease unwanted behaviours as well as developing new behaviours) Examples of procedures that can decrease unwanted behaviours include:

Prompting: prompts are supplementary antecedent stimuli that are used to occasion a desired response (see examples of prompting procedures in above section).

Visual supports: a visual tool presented to support the individual. They can be used to prompt or prime a desired response. This can include but is not limited to pictures, written words, transitional cues, schedules, gestures and choice boards. For example, the calendar in your phone is a visual support, wearing a wrist support with a motivational quote is also a visual support.

Choice: giving the individual an opportunity to select something within their environment e.g.,

- within activity choice (e.g., choice of material to use within an activity)

- between activity choice (e.g., choice among different activities)

- when (e.g., choice of time for activity to occur)

- who (e.g., choice of person to be included/excluded in the activity)

Extinction procedures: see extinction section above. (Cooper et al., 2020)

Generalisation and Social Validity in ABA

Generalisation is the occurrence of the target behaviour under different, non-training conditions (i.e., across subjects, settings, people, behaviours, time). Generalisation increases the likelihood that the behaviour change will occur in all relevant situations (e.g., behaviour on the training pitch transfers to behaviour on the pitch on match day). Socially validity refers to the extent to which target behaviours are appropriate, intervention procedures are acceptable, and significant changes in target behaviour are produced. Socially validity includes individual’s satisfaction with the goals, procedure, and outcomes of programs and interventions. According to Wolf (1978), social validity can be assessed by:

- The social significance of the target behaviour (e.g., important behaviours to the individual)

- The appropriateness of the procedures utilised (e.g., implementing the correct procedures)

- The social importance of the results (results benefit the individual and team)

Conclusion

This paper has focused on providing a brief overview on the potential of ABA in sport settings. Effectively applying behaviour change procedures within sport settings can benefit the individual athlete as well as the overall team by increasing socially significant behaviour while decreasing unwanted and negative behaviours. ABA has the potential to provide individual athletes with opportunities to improve skills and promote generalisation of these skills from the training ground to match day. ABA in sport is better recognised within the United States, Canada and Australia. It is continuing to grow within Europe, the UK and Ireland and hopefully over the coming years we will see more professionals from the field of ABA empower others in our sports with their knowledge and experience. As stated by Van Houten et al. (1988) the overpowering value of ABA should be promoting independence. A continually evolving science of ABA can empower our athletes to improve their own behaviour on and off the field of play. Improving and developing positive behaviour while working to decrease unwanted behaviours will maximise the potential of each player while simultaneously enhancing the potential for the team to meet their goals and objectives throughout their season.

Author: Peter Sweeney

For further information contact Peter via email: [email protected]

References:

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M., M. and Risley, T.R. (1968) ‘Some Current Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis’, Journal of ABA, 1(1), pp. 91-97.

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T.E. and Heward, W.L. (2020). ABA (Third Edition). United Kingdom: Pearson Education.

- Dunlap, G., Kern, L. and Worcester, J. (2001) ‘ABA and Academic Instruction’, Focus on Autism and other Developmental Disabilities, 16(2), pp. 129-136.

- Fisher, W.W., Piazza, C.C., and Roane, H.S. (2011) Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis. Ebrary[Online].

- Johnstone, J.M., and Pennypacker, H.S. (1993). Strategies and Tactics of Behavioural Research (Second edition). Hillsdale New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Keenan, M., Dillenburger, K., Röttgers, H.R., Dounavi, K., Jónsdóttir, S.L., Moderato, P., J. A. M. Schenk, J., Virués-Ortega, J., Roll-Pettersson, L., and Martin, N. (2015) ‘Autism and ABA: The Gulf Between North America and Europe’, Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2, pp. 167-783.

- Kerr, K.P., Mulhern, B.F., and McDowell, C. (2000) ‘ABA. It Works, It’s Positive; Now What’s the Problem?’ Early Child Development and Care, 163(1), pp. 125-131.

- Roane, H.S., Ringdahl, J.E., and Falcomata, T.S. (2015) Clinical and Organizational Applications of Applied Behavior Analysis.

- Twyman, J. S. and Heward, W. L. (2016) ‘How to improve student learning in every classroom now’, International Journal of Educational Research, 87, pp. 78-90.

- Van Houten, R., Axelrod, S., Bailey, J., Favell, J., Foxx, R., Iwata, B., and Lovass, O.I (1988). The Right to Effective Behavioral Treatment. Journal of ABA, 21(4), pp. 381-384.

- Vargas, J.S. (2013) Behaviour Analysis for Effective Teaching. (Second Edition), New York and London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: the case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart, Journal of ABA, 11(2), pp. 203-214.

Got a Question?

Contact us for more information on DSS Coaching.